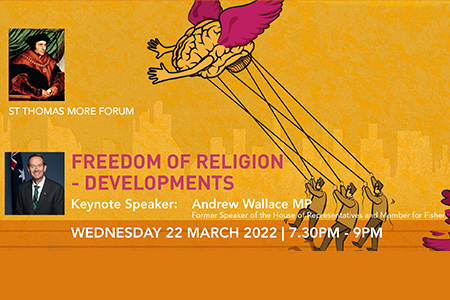

Thank you Bill and the St Thomas More Forum team for inviting me along to share tonight.

I’m honoured to be here in the parish whose namesake is that of another former Speaker of the House, albeit 500 years (in 1523) and 17,000 kilometres apart.

And of course St Thomas More was declared by Pope John Paul II in 2000 as the patron saint of statesmen and politicians.

Now I’m not sure if my good friend and flat-mate the Shadow Attorney-General and Shadow Minister for Indigenous Australians, Julian Leeser MP has in the Jewish faith a form of patron saint looking after him, but I’m very glad that St Thomas More has my back in Canberra. Would you please welcome Julian tonight, who has been sent here to make sure I don’t get myself into any trouble.

My Journey and Vocation

When I left school, I lived in a young Christian Community called Vaugirard and volunteered with the De La Salle Brothers, supporting marginalised young people who would have otherwise been living on the streets in Melbourne.

Believing that I was being called to a life of service to God and the Church, the following year I joined the Pallottine Order to become a Missionary Priest under the direction of Fr Walter Silvester. However after only having studied with the Pallottines for 8 months, Fr Walter came to the very quick realisation that it was doubtful that I was going to be able to fulfil my vows of poverty, chastity and obedience whereupon I was given the ‘DCM’ – the ‘don’t come Monday’.

That is a pretty special feat for a young man to be booted out of a monastery in the mid 1980s, when the Church was screaming out for young men to join the priesthood.

Whilst in the following years I agreed with that pretty sound assessment, some 36 years later as a former barrister with a successful commercial law practice, and now a Federal Member of Parliament who spends many months away from my wife and family, I am beginning to question the wisdom of Fr Walter’s discernment of not being able to fulfil those three vows after all.

After I left the Monastery, I became a carpenter and joiner, then a licensed builder, and eventually as I said a barrister practicing in commercial law. In 2016, I was elected the Federal Member for Fisher and have since worked hard to do my bit in making the world a better place, one day at a time.

Throughout my life, I have tried to remain true to the Latin motto of my old school St Bedes, where I was educated by the De La Salle Brothers: Per Vias Rectus, or “By Right Paths”.

In tackling issues such as eating disorder treatment, keeping kids safe online, reducing gambling harm, by holding big-tech, big-business, the banks and big-government to account on their role in preserving freedom and dignity, I have been compelled by the belief that walking the right path is often arduous, and lonely, but ultimately extraordinarily fulfilling.

Standing up for one’s convictions and beliefs sometimes lands us in trouble.

Sometimes, we feel like we walk alone in this journey of life. I often think of John the Baptist who remarked that he was a “lone voice in the wilderness, preparing the way for the Lord.”

There is no doubt that the strong faith that I grew up with, passed down to me from my parents and the De La Salle Brothers, has moulded me into the politician that I now am. You see, as strange as it might seem, I feel like I am back, albeit in a different guise, serving God and serving my community in what I regard to be the pinnacle of community service, in the Federal Parliament.

Yet it is not fashionable to talk of one’s faith any more. Once upon a time, the Labor Party was full of Catholics and proud to be so. The Liberal Party on the other hand used to attract more Protestants. But over the last 50 years, as the Australian community has become wealthier and more comfortable, our church numbers have declined.

It appears that many Australians either feel that God is no longer relevant in their lives, or many question His very existence. As is their right to do so. But equally, we people of faith have a right to practice our faith without fear of persecution.

Why Religious Freedom is Important

Why Religious Freedom is Important

Freedom of religion or belief is a “precious asset” that Government, Church, and Society must be united in protecting and promoting.

It’s an asset which has appreciated over time into the liberal democracy we hold so dear.

It is “one of the foundations of a democratic society” as the European Court of Human Rights found in the Dimitras case.

It’s an “essential human freedom” as President Franklin D Roosevelt declared.

Article 18 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights tells us that it is “far-reaching and profound” and that it is non-derogable and absolute.

It is a matter of fundamental human dignity.

As His Holiness Pope Francis shared,

“We believe that God created human beings equal in rights, duties and dignity, and he calls them to live as brothers and sisters and to spread the values of goodness, love and peace… there can be no peace without religious freedom.”

“Religious freedom is an authentic weapon of peace, with an historical and prophetic mission.”

“Religious freedom, an essential requirement of the dignity of every person, is a cornerstone of the structure of human rights.”

We cannot understate how crucial the freedom of religion or belief is to our national character, democratic order, and church teaching.

It is fundamental, precious and essential. And it is under threat.

Global Developments In Religious Freedom

Almost 1 in 3 countries face ongoing religious persecution, affecting 5.2 billion people – just under 2/3 of our population.

We know about some of these non-state actors who drive this persecution.

We think of ISIS and the Taliban, whose terror and transnational jihadist networks seek to establish “caliphates” at the expense of women, children, and those of differing beliefs.

As Deputy Chair of the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security, I have fought to see these groups named, shamed, and held to account.

Groups like Hamas, ISIS, Jemaah Islamiyah, and most recently, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps in Iran.

And more recently, the growing threat of right-wing extremists and white supremacists masquerading as Christian nationalists so tragically revealed in the murder of two police officers and one civilian on the Darling Downs in my home State of Queensland.

These groups, from across the political spectrum, employ online platforms to spread their radical ideas and to recruit domestic and international offenders.

Their insidious hatred of religious pluralism must be called out and stopped.

But intolerance is sometimes exacerbated or perpetrated by national governments.

Some of the worst are in our very own backyard, in the Indo-Pacific.

We know of China and North Korea, where Christians, Jews, Muslims and Falun practitioners face imprisonment, torture, labour camps, organ harvesting, sexual violence, and murder.

We know of Pakistan and Sri Lanka, where churches are subjected to mass casualty attacks with disturbing frequency.

At the 2022 International Ministerial Conference on Freedom of Religion or Belief, Australia joined over 30 democratic nations in committing to protecting this right, speaking out against violations of freedom, and to working together across borders and sectors to address challenges to freedom of religion.

That this issue hasn’t formed a more essential part of Australia’s foreign policy and human rights advocacy is, I think, a lost opportunity.

If we really want to be a force for moral good, regional security, and economic prosperity in our region, then promoting religious liberty ought to be a core human rights objective.

Domestic Developments In Religious Freedom

That also means that we do our bit to protect religious freedom here at home.

Pope Francis warned that the “radical secularity” which we see more and more in the West, risks consigning faith to the

“quiet obscurity of the individual’s conscience or relegates them to the enclosed precincts of churches, synagogues or mosques”.

Faith and religion, while not imposed or enforced by Government, should not be cause for discrimination.

Religion has a crucial role to play in society and in public life, as a moral compass for many and as a driver of civic duty and community-mindedness.

St Paul reminds us – and challenges us – that faith without deeds is dead. Faith without action is as good as having no faith at all.

General Comment 22 of the UN Human Rights Committee asserts that religious freedom must be protected – whether manifested behind closed doors or in community with others.

It should be encouraged by government, nourished by society, and a cause for celebration, not condemnation.

Religious Discrimination Legislation 2022

The previous Coalition Government sought to provide legally enshrined protections in a hard-fought and ultimately unsuccessful attempt at introducing religious discrimination legislation.

In November 2017, the previous Coalition Government appointed an Expert Panel, chaired by the Hon Philip Ruddock, to examine whether Australian law adequately protects the human right to freedom of religion.

That Panel concluded that there was an opportunity to further protect, and better promote the right to freedom of religion under Australian law and in the public sphere.

Its 20 recommendations formed the basis of the Coalition’s Religious Discrimination legislation, which was introduced in 2022.

What we sought was legislation that ensured Australians could not be discriminated against because of their religion – or lack thereof – as we went about our everyday lives.

As many of you know, that legislation went through an extensive consultation and review process.

It was opened for public consultation twice, submitted to a cross-party Parliamentary Committee review twice, and a survey conducted by the Human Rights Committee received over 48,000 submissions. 82% of those submissions were in support of the legislation.

I held two faith leaders’ roundtables in my own electorate to get a sense of how the Christian, Jewish, Muslim and Baha’i communities viewed the measures. They were of similar mind.

So, we brought it to a lengthy debate and vote in the House.

While some of the more eager political heads in the room tonight might have considered watching the entire debate, I’m sure most of you would have given up by midnight!

I was in the Speaker’s Chair for the deliberation, up until about 5.00am the next morning.

It was one of the longest debates in our Parliament for a generation.

However, the then Opposition moved an amendment to the Bill which would have stripped out protections for religious Australians expressing genuine statements of belief.

This would have weakened the Bill so much, that it would be more a statement of platitudes rather than statutory protections.

The Senate would have passed the amendment, despite its stall in the House.

For that reason, the Bill was withdrawn.

With emotions running high and parties not necessarily in-sync on these issues, it was not an unforeseeable outcome.

Antisemitism and Tolerance

But it’s not all-party politics and adversarial debate!

Just a couple of weeks ago, Parliament came together to reaffirm our commitment to the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s working definition of antisemitism.

We stood united in calling out religious and racial hatred.

The idea of antisemitism is repugnant to our egalitarian way of life because it is an assault on who we are as Australian people.

This is the case for all forms of religious discrimination.

I say it again: faith should be a cause for celebration, not condemnation.

Religious Freedom In The Future

Looking forward, I’m keeping a close eye on a few issues.

I’m particularly concerned about the future of faith in our schools. I am particularly interested in protecting a school’s right to decide who should and who should not teach our children in accordance with their adherence to the school’s particular faith and precepts.

Australia has largely, to date, been able to deliver a secular education system which engages meaningfully with faith communities and issues of faith.

We have protection for religious instruction, faith-based chaplains, and community partnerships to deliver volunteer programs in state schools.

These are programs which are accountable to government, school administration, and parents.

They are not able to evangelise, proselytise or promote one church or another.

And they have stood us in good stead.

I have heard time and again from young people who, but for the intervention of their chaplains, would not be here today.

I have seen how local churches have helped parents feed, clothe, and support their kids to undertake extra-curricular activities.

But without appropriate protection, these initiatives are under threat.

Aid to the Church in Need, which I’m sure some of you here support, is an international Catholic pastoral aid organization supporting the persecuted Church.

They said in their 2021 ‘Religious Freedom In The World Report’ that,

“Even though governments recognise that teaching world religions in schools reduces radicalisation, and increases interreligious understanding among young people, a growing number of countries have discontinued religious education classes.”

We are seeing this happen in Queensland, with State Government Ministers and Members calling for the end of voluntary religious instruction.

I was recently holding a Listening Post in my electorate, in an area no longer typically considered a Coalition stronghold.

There, a grandmother approached me concerned about this issue. As many across my electorate have since.

They understand that religious instruction is not about making converts of our young people.

For 113 years in Queensland, religious and values instruction has taught young people the Judaeo-Christian ethic of community-mindedness, service above self, and by walking this journey of life, by right paths.

These are values which are deeply ingrained within Australia’s culture and our institutions.

They are the foundation of our liberal democracy and common decency.

And in a so-called, ‘post-truth’ world, where moral absolutes are few and far between, perhaps we could do with more, not less, education around how to be a decent person.

A Future Religious Discrimination Bill?

Having said all of this, you might find strange what I am about to say. That is, protection from religious discrimination may not necessarily require a whole new package of legislation.

We saw how torturous this issue became in the 46th Parliament. I had and still have real concerns about enshrining these religious freedom rights in legislation. By doing so, such legislation risks becoming a double-edged sword, in which the rights afforded to sensible groups like the Parish of St Thomas More would be afforded to dangerous fringe movements such as the Noosa Temple of Satan up in my neck of the woods. With every action, there is a reaction.

If we legislate for religious freedom, we ought to be very cognisant of unforeseen consequences.

Ultimately, the system we have, balancing common law and statute is generally working. Sure there are your Israel Folau moments, or similarly you would recall where Essendon Football Club CEO Andrew Thorburn was effectively forced to resign just one day into his contract because of the views expressed by his church pastor.

Whilst it is easy to suggest that the law is not doing enough to protect people in these situations, ultimately, Folau received a multi-million dollar settlement from Rugby Australia for his troubles (Folau reportedly received $4M) whilst the Essendon Football Club issued a humiliating apology for its actions and paid an undisclosed settlement figure to an ethics institute.

The law is not perfect, but it never is. There is no silver bullet.

Whilst I am not suggesting that I would never ever support a Religious Discrimination Bill before the Parliament, we have to look very carefully at the sort of unintended consequences that such a codification would bring.

We must nurture the tolerant, vibrant, and shared civic values of freedom, faith, and family which have stood us in good stead for nearly 2000 years of Christendom.

Closing Remarks

Just as a person’s faith is innate and essential and crucial to their being, so too is the protection of that faith, which is core to the function of democracy.

For thousands of years, great societies have been marked by the way they protect and nurture people of faith. In doing so, they have seen a precious asset appreciate into vibrant democracies.

For thousands of years, grave tyrannies have been marked by the way they persecute and oppress religious groups. In doing so, they have faced strife and ultimately come undone.

The protection of religious freedom requires valiant hearts and vigilant minds.

And by meeting this evening to discuss such an important topic, I’m heartened to see such hearts and minds ready to take on the cause.

As St Thomas More said,

“What part soever you take upon you, play that as well as you can and make the best of it.”

Photos: Luke Donnelly

https://stthomasmore.au/freedom-of-religion-developments#sigProIdf9fe16ef97